Common terms explained

Standards New Zealand's online collection is made up of current, superseded and withdrawn versions of standards, some of which may be cited.

On this page

A range of similar standards showing their status

To find out what version you are looking for, depends on what is the standard and context you are using it in. Let’s look at what each label means.

Current

This is the latest version, and even if this is ten years old or more, if there has not been a revision since, it remains the most up to date version of that standard.

Superseded

This will not be the latest version of the standard, meaning that the standard has been revised and there is a newer version. We constantly review standards that are more than 10 years old to ensure they are current and continue to be fit for purpose and you can help determine their future through public consultation.

Withdrawn

The last version of the standard did not go through a further revision and is now decommissioned – while the good practice or guidance the standard may have provided at the time was relevant, it may no longer be useful or relevant for today’s needs, nor reflect technological advances. There will be no superseding standard for withdrawn standards.

Draft

Draft standards are the first version of a standard that the committee has developed and agreed is ready for testing with the wider user base through public consultation. While they may appear to be a whole standard, the committee are yet to incorporate public feedback which can vastly change the content and so the whole document is subject to change. Content in draft standards may not reflect the final content nor the agreed consensus of the development committee.

Cited

This means following the standard, or part of it, may be a requirement under law as it has been referenced in legislation or some other mandatory instrument. Typically this means the standard is referenced in regulations or the New Zealand Building Code.

Both superseded and withdrawn standards may be cited – here a requirement or guidance may need to point towards good practice of the time when the standard was relevant and before it was withdrawn or superseded. There may sometimes be a gap between when a new standard becomes available and when it replaces the citation of its predecessor in legislation, for example when the relevant Act needs to go through a process to be updated.

Examples of where standards may be cited include:

- referenced in Acts or regulations as legally mandatory

- referenced in Acts or regulations as ‘acceptable solutions’ or ‘means of compliance’. This ensures compliance with legislation but does not prevent the use of an alternative method, provided it meets the specified legislative criteria, for example the New Zealand Building Code

- used by a government agency to detail a required condition of contract with an external supplier

- incorporated into non-regulatory material as examples of leading practice or guidance for industry

- employed as a means of compliance with industry regulation, for example, specifying requirements for audit certification

- promoted as a means of dealing with legal liability issues, for example, compliance with various risk management standards may be cited in court as proof that all reasonable steps were taken.

How to know if a standard is cited

You can see instantly if a standard is cited from this symbol below its name in the webshop:

The cited symbol seen under the standard listing.

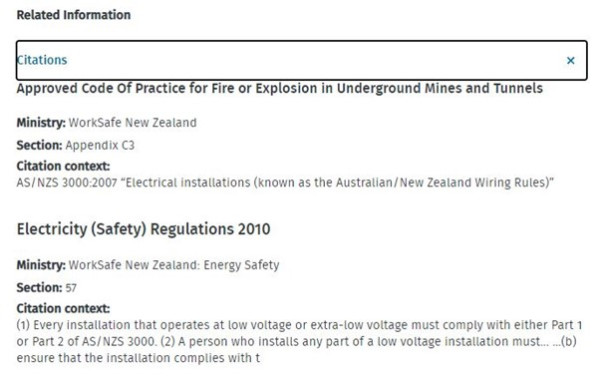

You can also find this information as a dropdown option on the webpage for the relevant standard:

This example shows the superseded AS/NZS 3000:2007 version which is referenced throughout multiple WorkSafe New Zealand documents.

De-jointed standards

There are occasions when a former Australian/New Zealand joint standard is either superseded or withdrawn in either Australia or New Zealand. The original version therefore only remains current within the one country where it has not been superseded or withdrawn.

Why old standards remain available

You may find you need to refer to withdrawn or superseded standards if the information it contains is relevant to understand how it was applied historically. That’s why we continue to provide withdrawn and superseded standards. As the guardians of standards we want those who might need to refer to old standards to have the choice and access. Some users need to compare one version to another and again providing access to withdrawn standards supports this.

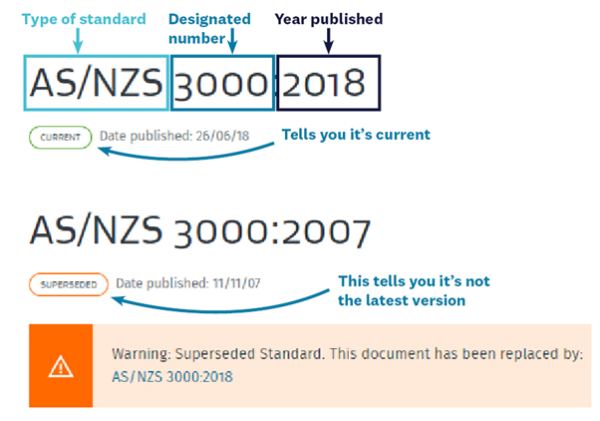

How to know if it’s the latest version

Every standard comes dated. If it has a green ‘current’ badge below you know it’s the latest version.

Any standards that have been superseded will have a warning box beneath the name informing you of this.

How to determine type, publication year and status of a standard.

Protecting the legitimacy of good practice

Standards New Zealand’s role goes beyond standards development. We are also guardians protecting copyright, providing access and updating reference to citations where they apply. While any organisation can produce their own standard, with Standards New Zealand as kaitiaki maintaining the integrity of the New Zealand, joint Australian/New Zealand and international standards, you can be confident what you are using is as agreed by the experts that put it together, legitimate and true.

Good practice doesn’t stop once a standard is developed. Standards reflect both the micro and macro environment they are used in. With continual technological and scientific advances and changes in policy and operating environments, standards will continue to evolve and new ones emerge to reflect the changing world.

Other terms

ICS codes

The International Classification for Standards (ICS) is a convention managed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and used in catalogues of international, regional, and national standards and other normative documents. It is essentially a standardised coding system for standards that can assist with search criteria and cataloguing.

Amendments

Sometimes small changes might need to occur to a standard that either make them more appropriate for a regional or specific need, for example, with international standards, or that factor in small changes or corrections between issues. Amendments save changing the entire document where it may not need changing.

Normative

Normative elements are those that are prescriptive. These show you how to comply with the standard or, if the standard is referenced in legislation, how to follow the law.

Normative elements will often use phrases like:

- Shall – indicates a requirement to be followed for conformity.

- Should – indicates a recommendation which the user is encouraged to follow.

- May – indicates a permission or option to follow as described.

It is the first of these words, ‘shall’, that is the cornerstone of normative content.

If something is a requirement of the standard why isn’t the word ‘must’ used? This goes to the heart of what a standard is. While legislation requires you to do something a particular way, the standard itself is not actual legislation, it is merely a tool towards meeting or complying with it, written with more of a focus on good practice. Sometimes standards can be one of a number of ways to meet compliance, therefore you are voluntarily choosing to be compliant and choosing to use this particular method hence shall rather than must.

Examples of normative content include product conformity and batch testing requirements for bicycle helmets in AS/NZS 2063:2020 Helmets for use on bicycles and wheeled recreational devices and the safety requirements of remote controls for electric toys in AS/NZS 62115:2018 Electric toys – Safety. Here, when an item is designed specifically for safety or where safe use is paramount, optional content could leave ambiguity that would undermine the standard. N

early every standard contains normative information. This is the purpose of standards, to spell out good practice in such a way that is clear what is required to follow it.

Informative

Informative elements are those that provide useful or interesting information or are descriptive and offer help to understand concepts. They can also include recommendations, suggested good practice that a reader need not follow to conform to the standard.

Typically, informative information may be supplemental, offering additional guidance, recommendations, or commentary either as written descriptions or illustrations. The word ‘should’ may be used in informative material, but not ‘shall’ – this is not material a user is required to follow to comply with the standard. It is there to complete the picture and help make sense of the normative requirements.

Understanding normative and informative

So while both types of content are ultimately used to offer good practice advice and guidance (that’s what standards are for) you now know whether you are being told to do something, advised to do something a particular way or helpfully informed of some of the background. Semantics – or the specific meaning of words – matters when safety, reliability, interoperability and efficiency are at stake. Normative content strives for clarity, spelling out what to do. Informative content helps you see the bigger picture.